History of Architecture V. - Neo-Revivals/Pre-Modernism

“I have therefore evolved the following maxim, and pronounce it to the world: the evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects

”

Modernism was a unique occurrence and a culmination of many colliding forces happening at once. We have come to know the term “Modern” as something very “clean” looking. Although this was part of the intent, the spirit behind the modernist movement was much more convoluted than opening up floor plans and adding clean lined finishes. It was fuelled by social and technological revolutions, that defined the 18th and 19th centuries and culminated into a complete set of ideals in the mid 20th century. Socially, people the world over organized themselves to “fight the power’s that be”. Unlike the reformation versus counter-reformation dispute of the 17th century, Modernism was a response to despotic monarchical rule rather than religion specifically, and it fueled the creation of socialist thought.Technologically, the 18th century Industrial Revolution produced a palette of vanguard materials for architects to design their buildings with: Wrought Iron, Structural Steel, and Reinforced Concrete.

Delacroix's painting from 1830, 'Liberty Leading the People', depicts the moment when French revolutionaries defeated King Charles the X of France. Revolutions were happening all over the world. As people began freeing themselves socially from monarchs and oligarchies, they also began freeing themselves artistically and architecturally by opposing established institutions and the images they represented.

The two centuries that led up to the birth of modernism in the 20th century gave the world the capacity and means to liberate themselves from both social and physical restrictions. It reflects the turmoil, confusion, and experimentation of societies around the globe. As the world social order began to reinterpret itself, architects too would be freed to create a new kind of architecture indicative of the times.

In the 21st century Modernism can be hard to define. Some use the word to mean anything not “classical”. Some use it to define anything designed from the 1950’s onward. Some specifically use it to describe the kinds of finishes used in a space. Popular culture has attached many interpretations that incorrectly define the Modernist Movement. At its core, Modernism is an extreme over-simplification of mass, surface and space. Forms were dwindled down to basic platonic shapes like squares and rectangles. All ornament was eventually removed. Architecture became a utility object only including its essential functioning parts. It became a “machine”, an adjective used during the 30’s as a metaphor for high-modern design. Modernist practitioners thought all ornament was superfluous and that any articulation not serving a building function was therefore not needed. Why? The ornament and articulation on buildings was often associated with politics statements, religious dogma, and other forms of cultural propaganda. These were the constructs people were not trying to eliminate but, to free themselves from. Modernist design was the physical manifestation of that. It was intended to be a liberating architecture. An architecture of the people. A socialist architecture. This removal of cultural propaganda and institutional grandeur was a slow process and there were many sub-styles developed before the high-modernist plateau in the 1930’s.

The Industrial Revolution produced wrought iron, steel, and reinforced concrete and completely “changed the game”. Buildings could get taller, contain more windows, and use less material because of the strength of these new components. The first structures to use these materials were monuments and public works like the Eiffel Tower in Paris and Brooklyn Bridge in NYC. But they were quickly adapted for use in buildings. Exterior building facades became thinner and structural support transitioned to steel framing instead of the traditional masonry bearing wall. Along with the perfection of the elevator, these materials produced structurally expressive spaces like Henri Labrouste’s National Library in Paris and the Wainwright Building from Louis Sullivan in Chicago, IL - the birthplace of the skyscraper building type. This moment in building science also marks the rise of the speciality engineer as the disciplines of civil and structural engineering were extracted from the direct responsibilities of the architect.

For centuries architecture had been the billboards of the social order to the governed, impressing upon the masses which ideals to fear, what to believe, and what was “truth.” Now more than ever was the opportunity to change that. In the late 19th century the world is influx, war is on the horizon and everything is up for debate and questioning, even architecture. There were those that stayed within the confines of classicism. But there were many who wanted to explore what architecture could be in this new age. Architects began playing with the possibilities and Art Nouveau was a style born out of this playfulness. Popular in France, Italy, Spain and Germany architects in this design philosophy departed from classical and Victorian principles, and pulled inspiration from the expressive Gothic and Baroque styles. Yet, Art Nouveau exceeds even the most organic gothic or baroque building. Art Nouveau encouraged free-flowing forms and curves that were based on plants and things found in nature, having the freedom to change direction and size at the discretion of the designer. The inventions of steel and concrete allowed this to happen, as a building's structural integrity became an artistic expression rather than something hidden from view. The subway stop canopies of the Paris Metro - designed by French Architect Hector Guimard - show off the traits of Art Nouveau with their slender iron profiles and apparent lightness. Catalan Architect Antonio Gaudi was a master of expressive natural forms both structurally and architecturally. His design for the Basilica de la Sagrada de Familia and Casa Mila in Barcelona are two of his most well known works in the Art Nouveau tradition.

Considered H.H. Richardson's finest architectural achievement, Trinity Church in Boston is an American treasure. There is a playfulness with how he moves through several historical styles in a search to find his own.

Crane Library in Boston has many of Richardson's signature moves like the arch entryway, the asymmetrical tower, the massiveness of stone, and the thickness of walls. His early contribution to modern architecture is portrayed in the grouped windows on the left. They almost form one long horizontal opening. This would be further developed in the coming century.

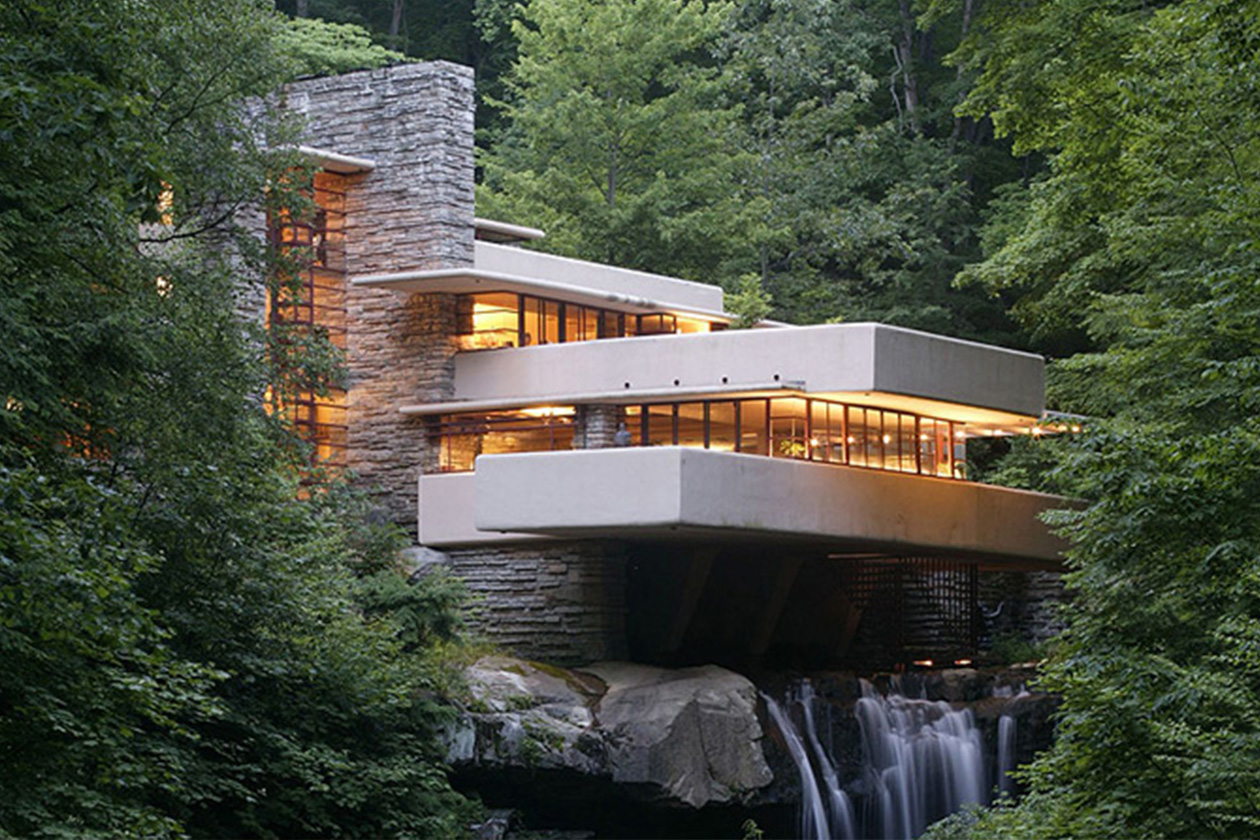

American architect Henry Hobson Richardson experimented with Romanesque architecture by exaggerating the sizes of the arch form and combining it with other voids and solids in very asymmetrical ways. He played with close groupings of horizontal windows, precursors to the elongated windows found in later modernist works. He relied on thick masonry walls to show the permanence of his architecture. His designs were so unique at the time that he was given his own style, Richardson Romanesque. Trinity Church in Boston is probably his most well known work. At the same time American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright is making his own re-interpretations of architecture. The American single family house at the time was based on the European tradition of having many separate rooms closed off from each other by walls. Wright explodes this idea and reconfigures the house as a free-flowing sequence of spaces centered around a focal point (usually a hearth). I suppose we can call him the grandfather of HGTV’s “open concept term”. Instead of keeping the house contained in a tightly “packed box”, Wright spaced the rooms of the home individual across the property. His buildings tended to be elongated, low to the earth, horizontal and free of obstructions in floor plan. These are the components of his signature Prairie Style. He was also a pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete in architecture. The majority of Wright’s work can be seen in the suburbs of Chicago. However, his Magnum Opus, the building that embodies all of his ideas is Fallingwater, a private house located just outside of Pittsburgh.

Considered Frank Lloyd Wright's masterpiece, Fallingwater is a triumph of modernism in both form and material innovation.

Key to Wright's space-planning and a primary trait to Modernist Architecture was the open plan building. Through the use of Poured in Place Concrete Wright was able to create a floor plan un-obstructed by interior columns like that of the Japanese Houses he admired.

A few decades before, Wright’s first employer and mentor - Louis Sullivan - and his business partner Dankmar Adler, were working though another architectural experimentation, the skyscraper. Steel allowed buildings to be built higher and use less material. Tall buildings of these heights had never been built before in this manner in human history and there was no precedent for how they should look. Sullivan created one, separating the building into three parts influenced by the classical column: The Base, the first two floors which contained stores and shops easily accessed from the street; The Shaft or middle, repetitive floors for offices and individual tenants; and the Capital or Top, where mechanical and other machinery would be located. You can also make the argument that this structure mimicked the three part Palazzi developed in the Italian Renaissance. Regardless, this diagram would serve as the model for designing tall buildings for decades. His Wainwright Building in Chicago and the Guaranty Building in Buffalo are great examples of his skyscraper diagram.

Three Parts of a Classical Order

Three Layers of the Italian Palazzo

Three Layers of the First Skyscrapers

![Fabric[K] Design](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5846fe37ff7c5046fc8b98e8/1585703506724-ACFUCZ5FH3AGY64QWIFZ/FabricK-Design_Logo_1500x600_All+Green.png?format=original)